Nine candles sit on the enormous white cake at the front of

the hall, their flames flickering as the chattering in the room quiets. Almost

all at once, sixty voices begin to sing “Happy birthday” together. All eyes are

focused on a dignified, elderly woman at one of the tables near the front;

Bernice Trollope, my grandmother, or as I affectionately know her, “Nana”. They

are celebrating 90 years of a remarkable life.

In 1921, Bernice was born in a tiny Norwegian settlement in

South Africa. Her father, a Christian missionary, was often away on missions in

Madagascar, leaving her mother to raise four children. There was no running

water or electricity, and her family was so poor that they couldn’t afford

shoes for her until she was five years old. But education promised a way out of

these dire circumstances. Bernice hitched a ride with several other kids from

her settlement on a horse-and-buggy that drove them to school every day.

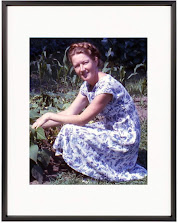

Classically Norwegian, Bernice was a plump-cheeked, big-boned

girl with auburn hair, ivory-skin and green eyes. She was very gentle and

obedient, and her Grade 1 teacher remarked in her report card that she was “An

excellent and disciplined pupil who takes herself too seriously.” Bernice fell

in love with languages, becoming fluent in Norwegian, English and

Afrikaans. She chose to become an English teacher.

Then, on September 4th, 1939, the Union of South

Africa declared war on Germany following Hitler’s surprise attack on Poland. The declaration of war changed the life of every South

African, and my grandmother voluntarily joined the army. She was trained to

operate supply vehicles and monitor radar, and was promoted to Sargeant.

During the war, she met a young engineer named William

Trollope. He was skinny and rather awkward-looking but was charming, brilliant

and had a fantastic sense of humor. He courted Bernice, but on a trip to Norway after the war ended, she became engaged to a Norwegian man. For some reason, the engagement fell through and

Bernice returned to South Africa. A gregarious and successful man that she had known since childhood began to court her, but she reconnected with William and accepted his marriage proposal instead.

Bernice envisioned a life in South Africa surrounded by her

vast extended family. She despised Apartheid and opposed the nationalist government, but despite this, she loved the country passionately; its lush, tropical countryside and vibrant way of life. She didn’t realize that William did not share the same attachments. Shortly after they were married, he secured a two-year position at an engineering firm in Quebec, Canada.

This came as a shock to Bernice. Quebec seemed very foreign; a French-speaking province in a distant country with a cold, snowy climate. Most important, she was deeply connected to her family, and this would mean leaving them behind. But since it was only for two years, Bernice accepted

the plan.

By now she and William had two children, including my

mother. The little family arrived in Sherbrooke, Quebec to a small apartment, in the dead of winter. Bernice struggled to adjust to their new life in Quebec. Her body, especially her sinuses, couldn't cope well with the extreme cold. But she didn't complain and instead adapted herself, starting a small English school for French children.

Bernice missed her family terribly during those years, especially her mother. Their only connection was through letters. And so it came as a huge shock when my grandfather decided

that they would settle in Canada permanently. He didn't see a positive future for South Africa. Bernice was devastated by the decision, but she came from a generation where the husband made the big decisions. Sadly, she couldn't even visit her family for many years because of her family responsibilities.

Meanwhile, William fell into severe clinical depression that

would last for most of the next two decades. Unfortunately, this was before the

time of effective treatments for major depressive disorder. When he returned from work, he

would immediately go to bed and only come out his room for supper. Bernice took on the responsibility for making family decisions, caring for the children and caring for William himself.

The family moved to Ancaster, but over the next years my grandmother's workload would only increase. William suffered through three different types of cancer brought on by a lifetime of smoking. When she was not taking care of him, she was volunteering at church. Her idea of Christianity is one of a loving, encompassing faith; last year, she voted in favour of allowing gay men and women to serve as priests within the Anglican church.

My grandfather died of leukemia in 2000. His depression had finally lifted in the last years of his life,

and he enjoyed a relaxed retirement in his Ancaster home. Although it was heartbreaking for my grandmother, it also marked the start of a wonderful new phase in her life. She loved to travel but had always stayed home to care for her husband.

And so we took a family trip to South Africa, crisscrossing

the country. We celebrated Nana’s 80th birthday in the city

of Pretoria and over a hundred family members and

friends attended. I met the other man who had courted my grandmother all

those years ago. Once she married William, he went on to marry another woman, had several kids and led a happy life in South Africa.

I can’t imagine how different her life would have been if

she had accepted his proposal. She could have stayed with her family in South

Africa and avoided the decades of hardship created by my grandfather’s

depression. Now, in her old age, she continues to be a nurturing influence on our tiny Canadian family; making countless pots of jams and blueberry pies, hosting family dinners and lending out her car. As a boy I would sleep over at her house every Friday, playing ridiculous word games with her while eating delicious heart-shaped waffles. She has always been a rock of stability in my life and the lives of all those close to her.

But now as I look at my grandmother in the church, I realize how

heavily time weighs upon her. Where once she was tall and strong, she is now stooped over and fragile, as if even a gentle breeze would

blow her over. Although I’m sure she’s in pain from her aching hip or from the

severe arthritis that wraps around her spine, she doesn’t show any trace of

complaint. She never does. Instead she smiles as she greets her guests.

For her, life has always been about grace, dignity and quiet

resolve.